TLDR:

Historically, markets have not been as forward looking as people think

Trailing stock earnings predict both the timing and magnitude of big moves

Earnings are vulnerable to a total collapse due to unprecedented falls in consumption, employment and capacity utilisation

This view is not widespread, so I expect risk off for the coming months

At the Watergate hearings, a question was asked that cut to the heart of the matter but is difficult to imagine being asked today: “What did the President know, and when did he know it”. These days, we know the answer in the case of the current white house incumbent. But we might usefully ask the same question of financial markets, because we’re often told that when prices are moving in the opposite direction that pundits anticipated, it’s because markets are looking forward to a time when the conditions that caused the pundits to take their view have reversed.

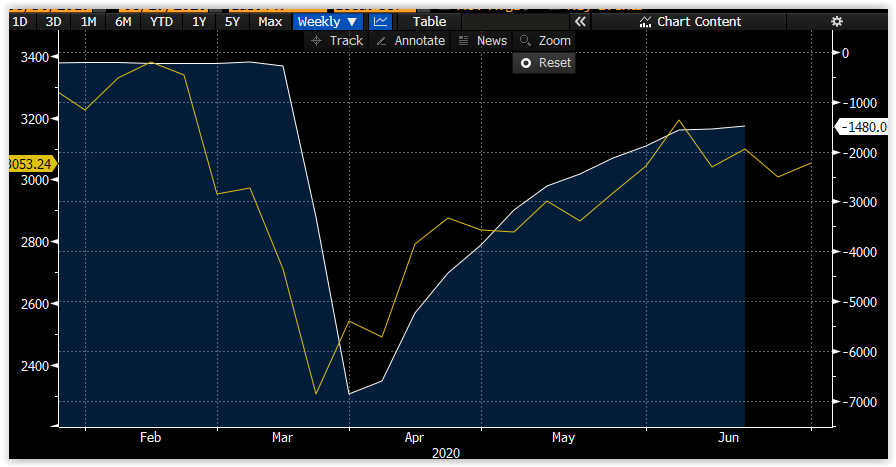

This explanation though leaves a puzzle. Here, the price of the S&P 500 in white, against estimated EPS (green) and trailing 12m EPS (yellow).

Even if I squint, I can find no reason to think the white line follows the green line closer than the yellow. In fact, at times when they diverge, price tends to follow realised EPS rather than expected EPS (Especially at market tops such as Q4 2007, Q2 2011). By itself that doesn’t invalidate the idea that markets are forward looking - analysts expectations may differ from those of actual buyers and sellers, and course expected earnings are only one point in time and don’t reflect a view about the entire future. It’s enough however to make me suspicious. Two more observations do the same. The first is my model of big stock market moves which explains the timing and magnitude of historical moves quite well using trailing earnings per share. The second is that it sure is strange that a supposedly forward looking market hasn’t spotted the trend higher in earnings and tried to get ahead of it. At this point a lot of people claim to have cottoned on to that fact that stocks mostly rise in the long run. In that case it’s strange that prices and earnings move by the same magnitudes. Both are 3x higher today than at the lows of 2008. For those that assert that this time is different, I’d like to point out one important similarity - prices and trailing 12m EPS have moved, since the start of the year, by roughly the same amount. EPS is down 7%, price 5%. Another coincidence in that chart however is the magnitude of the peak to trough move and the decline in expected EPS. On the 23rd of March, the S&P500 was down 34% from the highs, and expected EPS has stabilised around 30% lower than the February peak. The market, it appears, was forward looking enough to anticipate the extent to which forecasters would lower their estimated earnings! If anything, expectations about fundamentals were formed by price action rather than anticipating it.

What if prices simply follow what we know, when we know it? In late February we found out that a global pandemic was going to sharply curtail economic activity, but we did not know what the policy response would be. Stock prices declined. In late March, we found out what the policy response would be. In terms of actual information about the economic impact however, what did we really have? Weekly labour market data for one, and that coincided almost perfectly with moves in prices. Here, initial jobless claims (white, inverted) and the S&P 500 index (yellow):

Similar charts can be produced of the S&P against google searches for “Covid19”. The point here is not to promote a particular indicator, but to demonstrate that there have been plenty of factors that explain the price action in real time. What is considered “fundamental” is apt to change week by week in absence of information about earnings.

The coming months however will see remarkable declines in earnings. There is nothing controversial about that view, but I want to sketch out just how dramatic the fall could be. First, consider the extent to which US production is impaired, here the 25-54 employment rate in white and the capacity utilisation:

Not only is 1 in 10 25-54 year olds newly without a job, but so is 1 in 8 factories. Capacity utilisation has never been this low. The US has had a large reserve army of labour both at home and abroad for the past 10 years as the economy failed to recover from the 2008 financial crisis but they’re now joined by a reserve pool of capital that’s newly available. Capital is even stickier than people, but not infinitely so. Producers seeking to improve their margins to maintain earnings in lower volumes will invite some of the 1/3 of unemployed plant to be switched back on. Note that a 30 point increase in the empire manufacturing survey conditions index in April-May equated to only 0.8% of capacity being re-employed. Diffusion surveys miss the enormous difficulty of coordinating capital and labour back into production.

Government policy in the US has focused on ensuring firms do not go bust and households are able to maintain spending, and to that end they’ve added impressively to money balances across the economy. However, spending in nominal terms has fallen enormously compared to 2008. The peak of Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) in 2008 was in the summer. In the 3 months Sep-Dec, had businesses been expecting them to continue at August levels, $40bio of PCE went “missing”. In the 3 months of this pandemic, vs peak spending in Feb, the corresponding figure is 460bio. In 2008, that $40bio of missing PCE led to profits falling by $90bio over the quarter. It’s certainly going to be interesting to see how far they fall after an almost 500bio fall in PCE. Quarterly profits in the whole US economy are running at about 500bio, and have already fallen some $60bio from Q4 19 to Q1 20. It’s not beyond the realms of possibility that profits could be zero in Q2 across the whole economy. This is not a forecast, but neither is it something I’ve heard anybody talk about as the market rallies. According to Factset, S&P 500 earnings are projected to fall 44% from Q1 to Q2, so more sensible and sober analysts than me are seeing a powerful non linear relationship between falls in spending and profits.

So to come back to our question, what did we know and when did we know it? The moves we’ve had so far were explainable in terms of what was known at the time, not what was projected - at least not more than a couple of weeks out. The risk was known from early Feb but didn’t realise until real time economic activity measures turned south. It was possible to foresee policy intervention but the recovery didn’t begin until it started. The fact that these events frustrated many people’s predictions is absolutely normal, and doesn’t mean the market is looking ahead to the future so much as reacting faster than we can understand the present. In short, nothing about what’s happened to date in this crisis makes me think that the downside in earnings is priced. At the end of April I thought we had another month of risk on, and that’s no longer tenable. Until my view that lower earnings aren’t in the price is falsified, I’ll expect risk assets to suffer.

NB: This post is not investment advice and is not a trade recommendation. The views expressed here are my own and do not reflect those of my employer.